Loughary Lines

Loughary Stories

Bagan Stories

ThinkPint2.com home

|

|

You Say Oregon, We say Oregun

It is the simple truth that most travelers do not go through Oregon; they go to it. This has been true since white people began to explore the area that came to be known as the Oregon Country in the early 1700s.

Back Trail 300 Miles. Back Trail 300 Miles. |

Oregon was then and is now the long way to anywhere in North American, or anyplace else for that matter. The early Oregon trailers discovered this. The first Oregon Trail wagon train arrived in1837. It did not take the mind of a 1830 rocket scientist to figure out there was a more direct route from Independence, Missouri to the golden hills of California and it was not long before long the Oregon trail added a south branch prior to reaching Oregon. The story goes that a mound of stones topped with gold quartz marked the route south to California at the branch of the trail and a sign reading "To Oregon" pointed north. Those who could read went north.

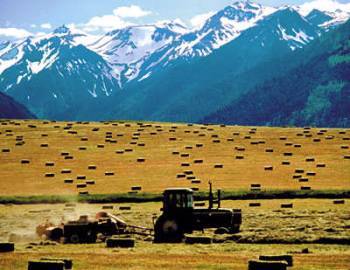

An other indication of "To not Through" tradition is suggested by the post-arrival behavior of some wagon trainers. After completing the four to six month hike across the plains and mountains to the Willamette Valley in Oregon, it was not uncommon for a few newly arrived travelers to rest a spell and then head back over the hill and settle in Eastern Oregon where they had been several months prior. They did so in sufficient number that the term "back trailers" was coined. My great, grandparents (Hiram and Martha) were members of this ambivalent group, remaining a relatively brief time in the Willamette Valley before high tailing it back to higher ground east of the Blue Mountains to raise horses in the Grande Ronde River Valley in what eventually became Union County. It was two generation later before their decedents wandered back into the Willamette the valley.

Geography and demographics being what they are, the routes in and out of Oregon remain mostly direct. Consider, for example, that there is not a direct train route from the Eastern United States to Oregon. Washington and California, yes, but not Oregon. There are no scheduled flights from Oregon to Canada or Mexico and as of this writing only one daily non-stop flight to New York City. At various times there have been direct flights to other East Coast Cities, Europe and Asia, but don't count on them. A direct trip to the outside world today requires connecting via Seattle, San Francisco or Los Angeles. Take a ship? No luck. The only major Oregon "seaport" is Portland, 60 miles up the Columbia River. Driving is the main option, but there is only one interstate freeway north from San Francisco to Seattle. It does go through Oregon and there are both northbound and southbound lanes which add considerable convenience.

Before you think this is a complaint, it is important to know that it is precisely the way many Oregonians want it. Tom McCall, a popular Oregon governor, made a Clint Eastwoodian reputation for himself by proclaiming that, "Everyone is welcome to visit Oregon, but don't get any funny ideas about staying!" or something to that effect. An important factor accounting for some of the relative isolation is demographics. Even though Oregon has 1.22 percent of the U.S. population (3.5 million), it ranks tenth in area among the 50 states (77,005 square miles). The majority of Oregonians live in a relative narrow western band of the state so there are enormous chunks of fascinating non-populated land to the east. The same is true of the state of Washington.

Eastern Oregon Eastern Oregon |

There may be historical precedents of this aloofness in the journeys of several early sea captain explorers who sailed to and fro around the northern Pacific Ocean looking for this and that. Household names including Bartolome' Ferrelo, Sir Francis Drake, Martin de Aguilar and Captain James Cook were in near shouting distance of the Oregon Country on more than one occasion. The famous Limey Captain George Vancouver passed by the mouth of the Columbia River in 1792 without stopping to explore. In May of 1792 both the American Captain Robert Gray and Vancouver were off the Oregon coast. According to O'Donnell, both noted a "great flow of muddy water fanning from the shore. Gray encountered Vancouver and informed him of his belief these muddy waters might well signify the mouth of the Great River of the West. The eminent navigator was not about to entertain such notions from the unknown American trader..." and sailed on. Gray with the strength of his conviction and probably a desire to put the Brit in his proper place guiding him, turned east and sailed towards a bar.

Captain Gray and the guys from Rediviva, May 11, 1792 |

"At four in the morning on 11 May Gray arrived at the river's mouth. Then, even more than now, the Columbia bar was one of the most treacherous on earth. They waited, four hours they waited, until there came the right convergence of currents, tide and wind. Gray gave the command, and the prow of his ship, the Columbia Rediviva, its figurehead holding before in the escutcheon of the American republic, crashed through the breakers into the waters of the Great River of the West, which from then on would be known as the Columbia."

In spite of Gray and other sea farers, most of the traffic to what would become the Oregon Territory was overland. Washington Territory, earlier part of the Oregon Territory, with the major sea way of Puget Sound welcoming ships, is another important part of the general development of the Oregon Territory and the specific nurturing of Oregon's island like character.

Early on in these stories from the Oregon Territory it would seems appropriate to clarify the origin of the word. The search is not especially useful, but nevertheless interesting. The source is the sixth edition of "Oregon Geographic Names" a volume just short of 1000 pages that is both informative and enlightening. It would be a nice touch for the residents if the name was a derivative of some Indian language term meaning "finest of all the best", but that is not even close. Instead, Lewis McArthur, the compiler of OGN states:

The most plausible present explanation of the name Oreogn is given by George R Stewart. In an article in American Speech, Apr. 1944 and Names on the Land, 1967, he propounds that the origin was an engraver's error naming the Ouisconsink (Wisconsin) River on certain French edition of Lahontan's map published in the early 1700s. In early editions the name was not only misspelled Quariconsint but also hyphenated after Quaricon–with the final syllable oddly offset. Stewart feels that Rogers (Major Robert Rogers, English army officer who copied and used map names) heard secondhand of the River Ouaricon that flowed west somewhere beyond the Great Lakes and that he mistakenly or carelessly transformed the word first to Ouragon and then to Ourigan. The odd nomenclature did not occur in the English editions of the map so if Rogers had seen one, he would have had no reason to suspect the Quaricon was merely the Wisconsin by another name. Previously for more than 50 years, the best opinion has been that the name originated from one of three sources, French, Indian or Spanish...French word for storm, ouragan...Spanish oye agua, hear the water...but this seems fanciful to the compiler. Thus the matter rests." (You have to admire McArthur's affirmative style.)

1. O'Donnell, Terence, 1997, The Balance So Rare, The Story of Oregon, Oregon Historical Society Press, Portland. See chapter 2.

2.O'Donnell, page 16.

3. McArthur, Lewis L.(1992), Oregon Geographic Names, Sixth Edition, Oregon Historical Society Press, Portland, Oregon.

|